JIRGA

****

Director: Benjamin Gilmour

Screenwriter: Benjamin Gilmour

Principal cast:

Sam Smith

Sher Alam Miskeen Ustad

Amir Shah Talash

Baheer Safi

Arzo Weda

Inam Khan

Country: Australia

Classification: M

Runtime: 78 mins.

Australian release date: 27 September 2018

Previewed at: Sony Pictures Theatrette, Sydney, on 30 July 2018.

The director Benjamin Gilmour’s return to northern Pakistan to shoot his next project, after his 2007 feature Son Of A Lion, ended up being relocated and re-written after funding fell through because the script was deemed too sensitive by the government - a scenario worthy of its own film perhaps? Not prepared to return to Australia empty-handed, Gilmour purchased a Sony A7S camera at a shopping mall in Pakistan and headed off to Afghanistan, considered one of the most dangerous places on the planet, to film Jirga. The title refers to the Pashtun village justice system, wherein a group of village or tribal elders convene a meeting to decide by consensus matters affecting their constituents, particularly matters of war.

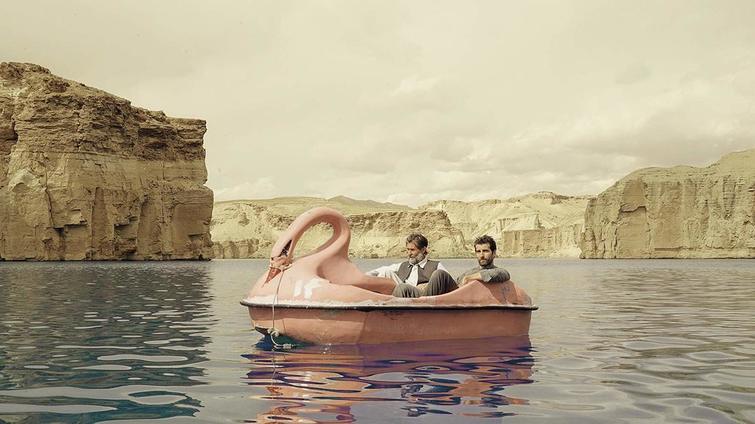

A former Australian soldier, Mike Wheeler (Sam Smith), has returned to Afghanistan determined to travel to a village near Kandahar to seek redemption from the family of an unarmed civilian he inadvertently killed during his tour of duty. Hiring a taxi in Kabul driven by an affable music-loving man (Sher Alam Miskeen Ustad), Wheeler asks him to take him south. The driver says it’s too dangerous but he will take him as far as the tourist area of Bamiyan. Once there, the ex-soldier offers him hundreds of US dollars to transport him further and the driver very reluctantly agrees but, along the way, Wheeler has to bolt into the desert at a Taliban roadblock. Collapsing from lack of water, he falls into the hands of the Taliban and awakes, shackled, in a cave. His captors are perplexed by his desire to seek forgiveness but decide to guide him to the vicinity of the village and leave him there to face the judgement of the Jirga, who will ultimately decide his fate under their law.

Jirga is an intensely personal journey, both for the director and Sam Smith. They were relying on Gilmour’s contacts to get them into the dangerous areas in which they wanted to shoot the film. The director explains that, once, “The police warned us they suspected militants, possibly ISIS, had been watching us and had planted IEDs at our shoot location. On one occasion we were told it would be too risky to return to a cave location, so we had to complete ten scenes in just three hours.” The script ably captures the complexity of the veteran’s situation while at the same time it succeeds in showing how things work in Afghanistan, a country not fully understood by the Western world. It concentrates on a man’s mission to seek redemption for a situation that haunts him and Gilmour says that these feelings aren’t uncommon in returned servicemen and women. “The motives for Mike’s return were inspired by the lingering sense of responsibility experienced by army veterans, from conflicts in Vietnam, Iraq and Timor-Leste. In my research I came across the stories of a number of Australian SAS veterans who had returned to Afghanistan, as civilians, to help rebuild villages damaged in conflict,” he says.

There’s another motivation at play in the making of the film, too. “Jirga is also intended to give the audience a new perspective on the lives of ordinary Afghan Muslims,” the director states. “It’s a great shame most westerner’s understanding of Afghanistan is only as a war zone. Of course, there’s active warfare in some provinces, but the country also boasts stunning natural landscapes and a rich culture of music and poetry. These aspects are so often overlooked yet so close to the hearts of Afghans.” He’s right about that. Jirga takes us into some of the most barren, yet stunningly beautiful country you can imagine, and shows us a new perspective on the lives of ordinary Afghan Muslims. Full credit must be given to Gilmour and Smith for accomplishing a credible piece of filmmaking under what must have been extremely difficult circumstances. The film doesn’t pretend to provide easy answers to the conflict in Afghanistan and, in Gilmour’s words, “doesn't attempt to neatly divide the good from the bad, but instead offers an insight into the character and motives of those we view as the enemy and the struggles of Afghans and the mercy found in their faith and traditions.”