THE LEUNIG FRAGMENTS

***

Director: Kasimir Burgess

Screenwriter: Kasimir Burgess

Principal cast:

Michael Leunig

Sunny Leunig

Kasimir Burgess

Philip Adams

Cathy Wilcox

Richard Tognetti

Country: Australia

Classification: M

Runtime: 97 mins.

Australian release date: 13 February 2020.

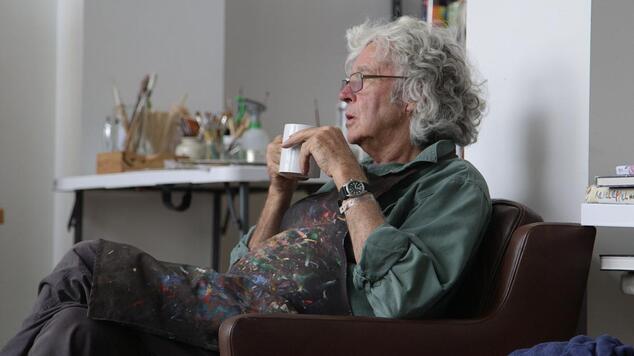

Cartoons can often speak louder than words, a few skilful lines revealing a great truth, and this is regularly seen in some of the best work by one of Australia’s ‘Living Treasures’, Michael Leunig. Kasimir Burgess’ documentary, The Leunig Fragments, filmed over a period of five years, combines interview footage with the man himself, lots of archival material and dramatic re-enactments of scenes from Leunig’s childhood. Amongst these fragments, we learn that Leunig is estranged from his families, both from his deceased parents (he didn’t go to their funerals) and his ex-wives and offspring (only one son is prepared to speak on camera about his father, but says he wouldn’t visit him), which may go some way to explaining Leunig’s somewhat distracted and discombobulated attitude to life itself. And that’s the thing: all these elements only go some way to painting a portrait of this enigmatic figure. The end result remains a little like a jig-saw puzzle with a few of the key pieces missing. The antithesis of a great cartoon.

Throughout this exposé, you are given the undeniable impression that Leunig is not at all comfortable opening up about himself and, in a telling scene, he explains that, perversely, artists often combine “the desire to communicate [with] the desire not to be found”. Which describes the cartoonist to a tee and sets the tone for Leunig’s Yoda-like responses to the director’s probing enquiries. He won’t, or can’t, answer questions directly. Burgess has said that he went through many “desperate times attempting to make a film about this elusive and sometimes prickly artist - my producer Philippa Campey and I had to fight for every moment. No lights, no sound recordist, just me and a camera delving through Michael’s meandering thoughts as he grappled with dying friends, divorce and a near fatal brain seizure.” His contemporaries, including Philip Adams, Andrew Jaspan, Richard Walsh and Cathy Wilcox, aren’t much help either, although they all speak highly of the man as incredibly perceptive, exhibiting an uncanny ability to convey strong messages through his cartoons on topics like friendship, life and death. Adams describes his friend’s unique skill as “weaponised whimsy.”

Another shortcoming of The Leunig Fragments is that it glosses over the controversy that some of Leunig’s drawings and opinions have garnered over the years, especially his questioning of the Victorian State Government’s ban on un-vaccinated children being allowed to attend kindergartens and child-care centres and a cartoon showing a mother using her mobile phone while her baby is left, abandoned on the pavement, suggesting that some mothers are more attentive to their social media and twitter accounts than they are to their children. Burgess has done his documentary, and his subject, a disservice by not pushing harder to get to the bottom of these issues.

Fans of Leunig’s who are intrigued by the man and his work may find themselves somewhat disappointed by this doc. Even the director admitted that, “My wish had been to make a film about a very particular human being and yet in a very Leunig narrative, I ended up getting lost and making a film about everyone and no one in particular.” And that’s one of the traps of documentary-making, the old conundrum that the very act of observation changes the nature of the thing being observed. Indeed, there’s more to be learned from The Leunig Fragments about the perils and pitfalls of shooting a factual feature on a living subject than there is about the man himself.

Screenwriter: Kasimir Burgess

Principal cast:

Michael Leunig

Sunny Leunig

Kasimir Burgess

Philip Adams

Cathy Wilcox

Richard Tognetti

Country: Australia

Classification: M

Runtime: 97 mins.

Australian release date: 13 February 2020.

Cartoons can often speak louder than words, a few skilful lines revealing a great truth, and this is regularly seen in some of the best work by one of Australia’s ‘Living Treasures’, Michael Leunig. Kasimir Burgess’ documentary, The Leunig Fragments, filmed over a period of five years, combines interview footage with the man himself, lots of archival material and dramatic re-enactments of scenes from Leunig’s childhood. Amongst these fragments, we learn that Leunig is estranged from his families, both from his deceased parents (he didn’t go to their funerals) and his ex-wives and offspring (only one son is prepared to speak on camera about his father, but says he wouldn’t visit him), which may go some way to explaining Leunig’s somewhat distracted and discombobulated attitude to life itself. And that’s the thing: all these elements only go some way to painting a portrait of this enigmatic figure. The end result remains a little like a jig-saw puzzle with a few of the key pieces missing. The antithesis of a great cartoon.

Throughout this exposé, you are given the undeniable impression that Leunig is not at all comfortable opening up about himself and, in a telling scene, he explains that, perversely, artists often combine “the desire to communicate [with] the desire not to be found”. Which describes the cartoonist to a tee and sets the tone for Leunig’s Yoda-like responses to the director’s probing enquiries. He won’t, or can’t, answer questions directly. Burgess has said that he went through many “desperate times attempting to make a film about this elusive and sometimes prickly artist - my producer Philippa Campey and I had to fight for every moment. No lights, no sound recordist, just me and a camera delving through Michael’s meandering thoughts as he grappled with dying friends, divorce and a near fatal brain seizure.” His contemporaries, including Philip Adams, Andrew Jaspan, Richard Walsh and Cathy Wilcox, aren’t much help either, although they all speak highly of the man as incredibly perceptive, exhibiting an uncanny ability to convey strong messages through his cartoons on topics like friendship, life and death. Adams describes his friend’s unique skill as “weaponised whimsy.”

Another shortcoming of The Leunig Fragments is that it glosses over the controversy that some of Leunig’s drawings and opinions have garnered over the years, especially his questioning of the Victorian State Government’s ban on un-vaccinated children being allowed to attend kindergartens and child-care centres and a cartoon showing a mother using her mobile phone while her baby is left, abandoned on the pavement, suggesting that some mothers are more attentive to their social media and twitter accounts than they are to their children. Burgess has done his documentary, and his subject, a disservice by not pushing harder to get to the bottom of these issues.

Fans of Leunig’s who are intrigued by the man and his work may find themselves somewhat disappointed by this doc. Even the director admitted that, “My wish had been to make a film about a very particular human being and yet in a very Leunig narrative, I ended up getting lost and making a film about everyone and no one in particular.” And that’s one of the traps of documentary-making, the old conundrum that the very act of observation changes the nature of the thing being observed. Indeed, there’s more to be learned from The Leunig Fragments about the perils and pitfalls of shooting a factual feature on a living subject than there is about the man himself.