LIVING

*****

Director: Oliver Hermanus

Screenplay: Kazuo Ishiguro, based on Akira Kurosawa’s film Ikiru, written by Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni.

Principal cast:

Bill Nighy

Aimee Lou Wood

Alex Sharp

Tom Burke

Adrian Rawlins

Hubert Burton

Oliver Chris

Country: UK/Japan/Sweden

Classification: PG

Runtime: 102 mins.

Australian release date: 16 March 2023.

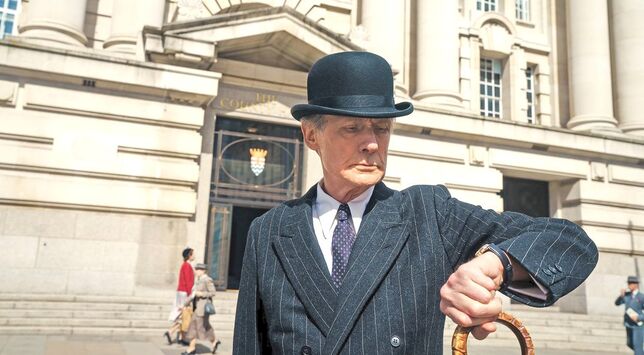

From the moment it opens, you know that Living is going to transport you to another time, a gentler, some would say more repressed, time. The title credits are in the style of British films of the early Fifties and, indeed, it is 1953 when we join hordes of pinstripe-suited, bowler hat-wearing civil servants as they gather on British train station platforms at precisely the same time each morning to travel to their stuffy offices in the city. One such group of bureaucrats is led by Mr. Williams (a career-defining performance from Oscar-nominated Bill Nighy), a long-serving paper-shuffler in a department of London County Hall. It seems these men, and they are almost all men, are there for one purpose only – not to get things done. If the slightest obstacle arises in someone’s application to improve things in their neighbourhood (this is post-war London and much of the city is yet to recover from the German bombing raids), their request is buried under a mound of files. We see all this when a group of women apply to have a children’s playground built in their impoverished area and they get shuffled from pillar to post without any advancement in their petition. And then Mr. Williams receives a terrible diagnosis – he has a terminal illness and may have as little as six months to live – and his approach to life changes radically. It’s as if he wakes up from a deep sleep.

This quiet, moving film is directed by the South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus and he has done an excellent job, but the real star of Living is the screenplay by Kazuo Ishiguro, the Nobel Prize-winning author of The Remains of the Day, Never Let Me Go and others. He moved to England from Japan at the age of five and was struck from an early age by the similarities between the British and Japanese cultures. The film’s co-producer, Stephen Woolley, explains that, “A common emotion between people in Japan and Britain, which I think Ishiguro has found, is that they both have the same stoic restraint. Japanese society and British society are based on a lack of effusiveness.” Talking of the script-writing process, Ishiguro jokingly says, “All the heavy lifting had been done. It’s kind of a translation job,” and he has, in fact, stuck pretty closely to the original story of Kurosawa’s 1952 masterpiece, while bringing his own insights into the dialogue. His work earned him a well-deserved Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay but it lost to Sarah Polley’s Women Talking.

Bill Nighy, like the great Takashi Shimura before him, brings tremendous dignity to the role of this repressed character who only learns to live when faced with his mortality. His long face seems purpose-built to convey the withdrawn, stiff personality of Mr. Williams, a cypher for the men of that period, raised to never reveal any inner emotion to the outside world. He’s even unable to tell his son (Barney Fishwick) the news of his fatal diagnosis. Little wonder that a young woman he knows from the office, Miss Harris (Aimee Lou Wood), lets him know that her nickname for him is ‘Mr. Zombie.’ Nighy delivers a magnificent performance and Wood, too, is excellent as the bubbly young woman who helps to reinvigorate the old man and who represents the changing face of English post-war society.

Living is a terrific achievement and its lessons are profound. Even its cynical ending conveys a message to the living.

Screenplay: Kazuo Ishiguro, based on Akira Kurosawa’s film Ikiru, written by Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni.

Principal cast:

Bill Nighy

Aimee Lou Wood

Alex Sharp

Tom Burke

Adrian Rawlins

Hubert Burton

Oliver Chris

Country: UK/Japan/Sweden

Classification: PG

Runtime: 102 mins.

Australian release date: 16 March 2023.

From the moment it opens, you know that Living is going to transport you to another time, a gentler, some would say more repressed, time. The title credits are in the style of British films of the early Fifties and, indeed, it is 1953 when we join hordes of pinstripe-suited, bowler hat-wearing civil servants as they gather on British train station platforms at precisely the same time each morning to travel to their stuffy offices in the city. One such group of bureaucrats is led by Mr. Williams (a career-defining performance from Oscar-nominated Bill Nighy), a long-serving paper-shuffler in a department of London County Hall. It seems these men, and they are almost all men, are there for one purpose only – not to get things done. If the slightest obstacle arises in someone’s application to improve things in their neighbourhood (this is post-war London and much of the city is yet to recover from the German bombing raids), their request is buried under a mound of files. We see all this when a group of women apply to have a children’s playground built in their impoverished area and they get shuffled from pillar to post without any advancement in their petition. And then Mr. Williams receives a terrible diagnosis – he has a terminal illness and may have as little as six months to live – and his approach to life changes radically. It’s as if he wakes up from a deep sleep.

This quiet, moving film is directed by the South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus and he has done an excellent job, but the real star of Living is the screenplay by Kazuo Ishiguro, the Nobel Prize-winning author of The Remains of the Day, Never Let Me Go and others. He moved to England from Japan at the age of five and was struck from an early age by the similarities between the British and Japanese cultures. The film’s co-producer, Stephen Woolley, explains that, “A common emotion between people in Japan and Britain, which I think Ishiguro has found, is that they both have the same stoic restraint. Japanese society and British society are based on a lack of effusiveness.” Talking of the script-writing process, Ishiguro jokingly says, “All the heavy lifting had been done. It’s kind of a translation job,” and he has, in fact, stuck pretty closely to the original story of Kurosawa’s 1952 masterpiece, while bringing his own insights into the dialogue. His work earned him a well-deserved Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay but it lost to Sarah Polley’s Women Talking.

Bill Nighy, like the great Takashi Shimura before him, brings tremendous dignity to the role of this repressed character who only learns to live when faced with his mortality. His long face seems purpose-built to convey the withdrawn, stiff personality of Mr. Williams, a cypher for the men of that period, raised to never reveal any inner emotion to the outside world. He’s even unable to tell his son (Barney Fishwick) the news of his fatal diagnosis. Little wonder that a young woman he knows from the office, Miss Harris (Aimee Lou Wood), lets him know that her nickname for him is ‘Mr. Zombie.’ Nighy delivers a magnificent performance and Wood, too, is excellent as the bubbly young woman who helps to reinvigorate the old man and who represents the changing face of English post-war society.

Living is a terrific achievement and its lessons are profound. Even its cynical ending conveys a message to the living.